|

Welcome to my blog! I've decided to use this space as a how-to for creating and running perception experiments, both as a way to organize my thoughts and as a way to help you, random person on the internet. I'm writing this for an audience (assuming you exist) that has some knowledge of L2 phonology, but no practical experience running experiments. So let's get started! First of all, if you're excited to start a perception experiment, as we all should be, you have a research question in mind that you want answered. This research question will determine what kind of task you should use, as different types of tasks examine different levels of processing. In this post I'll outline common types of research questions along with their corresponding appropriate task(s). 1. What sounds in the L1 are closest to these non-native/L2 sounds? Perceptual Assimilation:

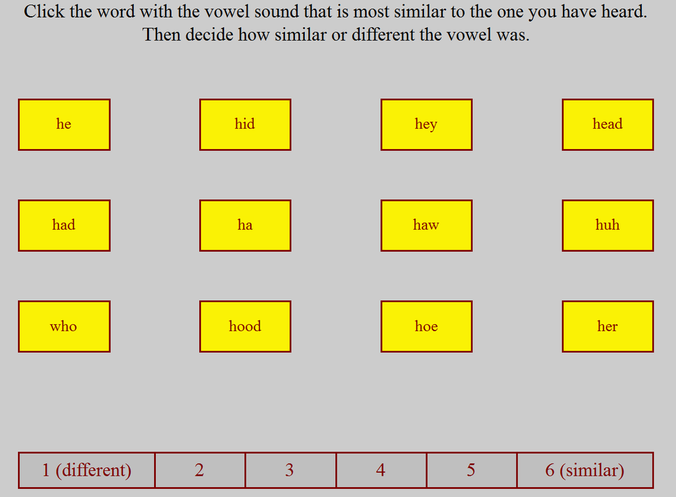

Additional information: Studies that examine the relationship of L1 sounds to non-native or L2 sounds are typically carried out under the theoretical framework of the Perceptual Assimilation Model (PAM) (Best, 1995) or its adaptation to L2 learning (PAM-L2; Best & Tyler, 2007). Researchers often use the relationship of L1 to non-native/L2 categories to make predictions about how accurately various contrasts will be discriminated (e.g. Tyler et al., 2014). We've found that perceptual similarity of non-native/L2 sounds to each other, rather than to L1 sounds, is a better predictor of discriminability. This can be computed either indirectly through perceptual assimilation overlap scores (how often two non-native sounds were perceived as the same set of L1 categories; see Levy, 2009, for more about this analysis) or through the results of perceptual similarity tasks. 2. What non-native/L2 sounds are perceived as similar to each other? Similarity Judgment:

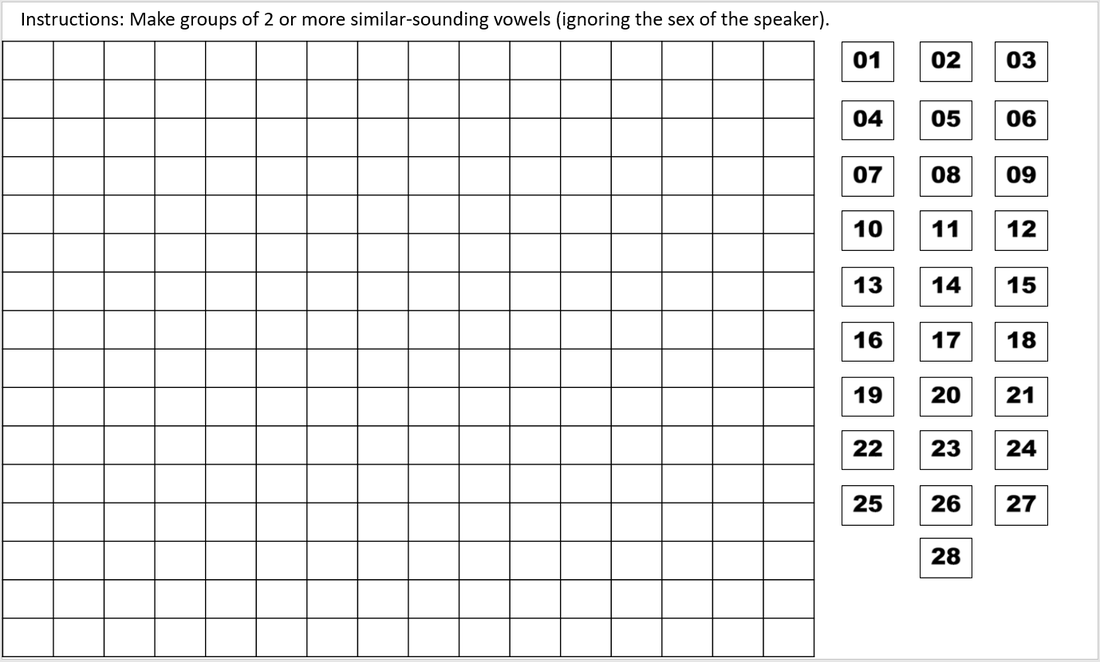

Free Classification (aka Free Sort):

Additional information: These kinds of research questions most closely align with the Speech Learning Model (SLM) (Flege, 1995). Similarity judgment has been used both with natural stimuli (Fox, Flege, & Munro, 1995) and with synthetic stimuli on a continuum in order to examine how the perceptual space is warped by the L1 (Iverson et al., 2003). Free classification or similarity judgment tasks have the advantage of not imposing a predetermined number of categories or category labels on the participant. A multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) analysis allows the researcher to investigate how many dimensions the participants are using to determine the similarity of stimuli. Dimension scores can then be correlated with acoustic properties (e.g. F1, roundedness) to determine what these dimensions represent (Daidone, Kruger, & Lidster, 2015; Fox, Flege, & Munro, 1995). 3. Can listeners discriminate this non-native/L2 contrast? AX:

ABX (AXB, XAB):

Oddity:

Oddball:

Sequence recall:

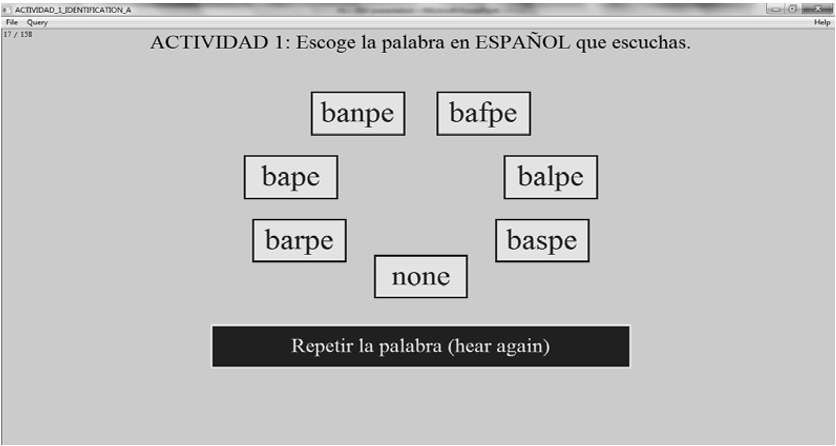

Additional information: Different discrimination tasks allow for different processing strategies, and tasks can be modified to increase or decrease the amount of cognitive load. Strange and Shafer (2008) have a nice summary of perception tasks and the effects of different experiment conditions on performance. An increase in cognitive demand reduces the possibility that participants can use acoustic cues to complete the task. Physically different stimuli, multiple talkers, and embedding the stimuli in a context are all ways to force participants to process the contrast phonetically or phonologically, rather than searching for an acoustic match. Cognitive demand can also be increased through a higher memory load. For example, at the higher sequence lengths in a sequence recall task, even the native speakers are not at ceiling. The effect of interstimulus interval (ISI) is somewhat mixed in the literature, with some studies finding a difference in performance at different ISIs (e.g. Werker & Tees, 1984) and others not (e.g. Tyler & Fenwick, 2012). Overall, it seems that both an extremely short ISI (0ms) and an extremely long ISI (1500ms) make the task more difficult. In my experience, an ISI of 1000ms is already very boring, and participants are more likely to let their attention wander. In general, AX tasks are easiest for participants, with difficulty increasing for AXB and oddity, followed by sequence recall, particularly at higher sequence lengths. For example, in a series of studies Dupoux and colleagues found that French learners of Spanish could discriminate a stress contrast in an AX task with a single talker, but performed worse in an ABX task with multiple talkers. In a sequence recall task, the performance of French participants was negatively affected by an increased sequence length, as well as by the amount of phonetic variability present in the stimuli. In our research, we've found that the results of an AXB task with a 1000ms ISI and an oddity task with a 400ms ISI were very highly correlated. Given this, I suggest using an oddity task since 1) the task is more intuitive, so participants are less confused by it and 2) chance level is much lower (25% for oddity vs. 50% for AXB), so a higher variability in scores is possible with oddity. Results of discrimination tasks are typically reported in terms of accuracy or d' (d-prime) (or A'). d' is often a better metric because unlike accuracy rates, it is not affected by a participant's bias to answer one way or the other, e.g. a participant that responds 'same' to all trials. 4. Can L2 learners identify these L2 sounds? Identification:

5. Can L2 learners represent this contrast in their mental lexicon? Lexical decision:

Word Learning:

I hope this summary of perception tasks has been helpful! I also recommend checking out "A Brief Primer on Experimental Designs for Speech Perception Research" by Grant McGuire at UC Santa Cruz. As you're deciding on a perception task, keep in mind that researchers frequently pair tasks together to look at different levels of processing. A study may examine, for example, both participants' ability to discriminate a contrast and their ability to represent this contrast in lexical representations. Previous research has found that discrimination is easier than identification, which in turn is easier than any task tapping a lexical level of processing (Díaz et al., 2012; Ingram & Park, 1997; Sebastián-Gallés & Baus, 2005). References

Best, C. T. (1995). A direct realist view of cross-language speech perception. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research (pp. 171-204). Timonium, MD: York Press. Best, C., & Tyler, M. (2007). Nonnative and second-language speech perception: Commonalities and complementarities. In O.-S. Bohn & M. Munro (Eds.), Language experience in second language speech learning: In honor of James Emil Flege (pp. 13-34). Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Bradlow, A. R., Akahane-Yamada, R., Pisoni, D. B., & Tohkura, Y. I. (1999). Training Japanese listeners to identify English /r/ and /l/: Long-term retention of learning in perception and production. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 61(5), 977-985. Broersma, M. (2012). Increased lexical activation and reduced competition in second-language listening. Language and cognitive processes, 27(7-8), 1205-1224. Broersma, M., & Cutler, A. (2008). Phantom word activation in L2. System, 36(1), 22-34. Clopper, C. G. (2008). Auditory free classification: Methods and analysis. Behavior Research Methods, 40(2), 575-581. Daidone, D. & Darcy, I. (2014). Quierro comprar una guitara: Lexical encoding of the tap and trill by L2 learners of Spanish. In R. T. Miller, K. I. Martin, C. M. Eddington, A. Henery, N. Marcos Miguel, A. M. Tseng, …D. Walter (Eds.), Selected Proceedings of the 2012 Second Language Research Forum (pp. 39-50). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. Daidone, D., Kruger, F., & Lidster, R. (2015). Perceptual assimilation and free classification of German vowels by American English listeners. In The Scottish Consortium for ICPhS 2015 (Eds.), Proceedings of the 18th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. Glasgow, UK: Glasgow University. Díaz, B., Mitterer, H., Broersma, M., & Sebastián-Gallés, N. (2012). Individual differences in late bilinguals' L2 phonological processes: From acoustic-phonetic analysis to lexical access. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(6), 680-689. Dupoux, E., Sebastián-Gallés, N., Navarrete, E., & Peperkamp, S. (2008). Persistent stress ‘deafness’: The case of French learners of Spanish. Cognition, 106(2), 682-706. Escudero, P., & Vasiliev, P. (2011). Cross-language acoustic similarity predicts perceptual assimilation of Canadian English and Canadian French vowels. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 130(5), EL277-EL283. Flege, J. E. (1995). Second language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research (pp. 233-277). Timonium, MD: York Press. Fox, R. A., Flege, J. E., & Munro, M. J. (1995). The perception of English and Spanish vowels by native English and Spanish listeners: A multidimensional scaling analysis. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97(4), 2540-2551. Hayes-Harb, R., & Masuda, K. (2008). Development of the ability to lexically encode novel second language phonemic contrasts. Second Language Research, 24(1), 5-33. Ingram, J. C., & Park, S. G. (1998). Language, context, and speaker effects in the identification and discrimination of English /r/ and /l/ by Japanese and Korean listeners. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 103(2), 1161-1174. Iverson, P., & Kuhl, P. K. (1995). Mapping the perceptual magnet effect for speech using signal detection theory and multidimensional scaling. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97(1), 553-562. Iverson, P., Kuhl, P. K., Akahane-Yamada, R., Diesch, E., Tohkura, Y. I., Kettermann, A., & Siebert, C. (2003). A perceptual interference account of acquisition difficulties for non-native phonemes. Cognition, 87(1), B47-B57. Kuhl, P. K. (1993). Innate predispositions and the effects of experience in speech perception: The native language magnet theory. In Developmental neurocognition: Speech and face processing in the first year of life (pp. 259-274). Springer: Netherlands. Kuhl, P. K., Conboy, B. T., Coffey-Corina, S., Padden, D., Rivera-Gaxiola, M., & Nelson, T. (2008). Phonetic learning as a pathway to language: New data and native language magnet theory expanded (NLM-e). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 363(1493), 979-1000. Levy, E. S. (2009). On the assimilation-discrimination relationship in American English adults' French vowel learning. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 126(5), 2670-2682. Pallier, C., Colomé, A., & Sebastián-Gallés, N. (2001). The influence of native-language phonology on lexical access: Exemplar-based versus abstract lexical entries. Psychological Science, 12(6), 445-449. Schmidt, L. B. (2011). Acquisition of dialectal variation in a second language: L2 perception of aspiration of Spanish /s/ (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. Sebastián-Gallés, N., & Baus, C. (2005). On the relationship between perception and production in L2 categories. In A. Cutler (Ed.), Twenty-first century psycholinguistics: Four cornerstones (pp. 279-292). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Showalter, C. E., & Hayes-Harb, R. (2013). Unfamiliar orthographic information and second language word learning: A novel lexicon study. Second Language Research, 29(2), 185-200. Strange, W., Bohn, O. S., Nishi, K., & Trent, S. A. (2005). Contextual variation in the acoustic and perceptual similarity of North German and American English vowels. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 118(3), 1751-1762. Strange, W., & Shafer, V. L. (2008). Speech perception in second language learners: The re-education of selective perception. In J. G. Hansen Edwards & M. L. Zampini (Eds.), Phonology and second language acquisition (pp. 153-192). Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins. Tyler, M. D., & Fenwick, S. (2012). Perceptual assimilation of Arabic voiceless fricatives by English monolinguals. In INTERSPEECH 2012 (pp. 911-914). Tyler, M. D., Best, C. T., Faber, A., & Levitt, A. G. (2014). Perceptual assimilation and discrimination of non-native vowel contrasts. Phonetica, 71(1), 4-21. Weber, A., & Cutler, A. (2004). Lexical competition in non-native spoken-word recognition. Journal of Memory and Language, 50(1), 1-25. Werker, J. F., & Tees, R. C. (1984). Phonemic and phonetic factors in adult cross‐language speech perception. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 75(6), 1866-1878.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI like sounds. Here I'll teach you how to play with them and force other people to listen to them. For science. Archives

August 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed