|

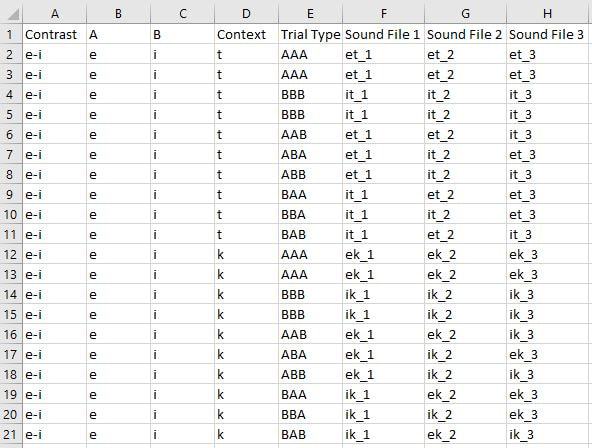

Once you've chosen a perception task, it's time to make stimuli for it. How many stimuli do I need? The answer to this question isn't simple. You'll need to strike a balance between getting a sufficient amount of data and how long you can reasonably expect people to sit and do your experiment. In our lab, we generally have to recruit participants with extra credit, the promise of snacks, and desperate pleas, so any experiment over an hour or an hour and 15 minutes is unlikely to have many people sign up. If you can pay people they'll be more willing to do a longer experiment, but that means more money you'll have to shell out for each person. Since your experiment is likely to be made up of two or more tasks, such as both discrimination and lexical decision plus a background questionnaire, each task in itself shouldn't be longer than about 25 minutes, if possible. Shorter tasks will also prevent participants' attention from wandering too much, which means more reliable data. A 20-minute AXB or oddity task is already very boring even with a break, and with difficult contrasts it can also be mentally taxing and demoralizing. I know some psychology experiments have participants doing one repetitive task for an hour (how?!), but if you don't want participants to constantly time out on trials because they are falling asleep or trying to surreptitiously check their phones, keep it shorter. For most kinds of tasks, to calculate how long it will take you'll need to take into account the number of trials and how long each trial lasts. When figuring out how many trials you need, keep in mind that for AX, you should have an equal number of same and different trials, and with lexical decision you should have an equal number of word and nonword trials. For ABX-like tasks you'll need to balance the order of stimuli so that all six possible orders of stimuli are present: ABA, ABB, AAB, BAB, BAA, BBA. In other words, if your contrast is [e] vs. [i], in one trial the order will be [kek], [kik], [kek] (ABA), in another [kek], [kik], [kik] (ABB), etc. This ensures that X is equally likely to be A or B and that the order of presentation does not influence the results. Oddity tasks should also have the six possible orders of stimuli, plus all-the-same trials (AAA, BBB). You can either balance the number of same vs. odd-one-out trials or balance how often each button is the correct answer (first sound is different, second sound is different, third sound is different, or all the same). I prefer the second option, since participants are likely to hear difficult contrasts as same trials anyway. Note that the types of trials don't have to be perfectly balanced; for example, you could do 12 different trials (4, 4, and 4 in each position) and 8 same trials. Just make sure they aren't too disparate. For the number of conditions, don't forget that you need a control condition to show that your task is working. In our experiments, we've tested up to 10 contrasts in a discrimination task. I think this is near the upper limit, since having more data points per condition is always better, especially if you plan to do individual-level analyses, and for each condition you add, the less trials per condition you'll be able to fit in. Around 16-20 trials per condition is a good number, which may be split into a couple different phonetic contexts. Here's an example from our latest oddity task: 10 contrasts (e.g. /u/ vs. /y/) x 10 trials per contrast (2 AAA, 2 BBB, AAB, ABA, ABB, BAA, BBA, BAB) x 2 contexts ([tVhVt], [kVhVk]) = 200 trials It's helpful if you map out your trial set up in Excel, like this: You'll also need practice trials so that participants can learn how to do the task. About 8 or 10 is enough. For some tasks you'll need filler trials as well, particularly if you are only testing a small number of conditions. The point is that you don't want participants to figure out what you're testing and start employing an explicit strategy for completing the task.

In order to calculate how long each trial will take, you add the length of the sound files in each trial + interstimulus intervals (pauses between stimuli) + intertrial interval (pause between trials). For example, in our oddity task each word lasts about 600-750 ms, so let's use 700 ms as an estimate. With an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 400 ms and an intertrial interval (ITI) of 500 ms, that means each trial takes 700 ms for the first stimulus + 400 ms pause + 700 ms for the second stimulus + 400 ms pause + 700 ms for the third stimulus + 500 ms after the trial. In other words, 700 ms x 3 + 400 ms x 2 + 500 ms = 3400 ms, or 3.4 seconds per trial. Now you can calculate how long the all trials will take combined. 3.4 s x 200 trials = 680 s, or 11.33 min. With the instructions, practice trials, and a break, that's about 15 minutes for the oddity task, which is totally doable. Words or nonwords? If your task is examining discrimination, similarity, or categorization, it's best to use nonwords. By using nonwords, you won't need to worry about lexical frequency effects, such as the fact that people respond faster to more frequent words. Also, if you're testing learners and a control group of native speakers, the lexical knowledge of each group will likely vary, possibly affecting your results. For a lexical decision task you'll obviously need words, but you'll also need non-words both as near-words to test lexical knowledge and as fillers. Tips for making nonwords:

Tips for choosing real words:

Tips for both words and nonwords:

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI like sounds. Here I'll teach you how to play with them and force other people to listen to them. For science. Archives

August 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed